Fundamental Analysis

The following headlines have been reprinted from The Penn Wealth Report and are protected under copyright. Members can access the full stories by selecting the respective issue link. Once logged in, you will have access to all subsequent articles. Remember, when in any publication you can create an eBook for download by selecting the PDF option in the purple bar at the top of the page.

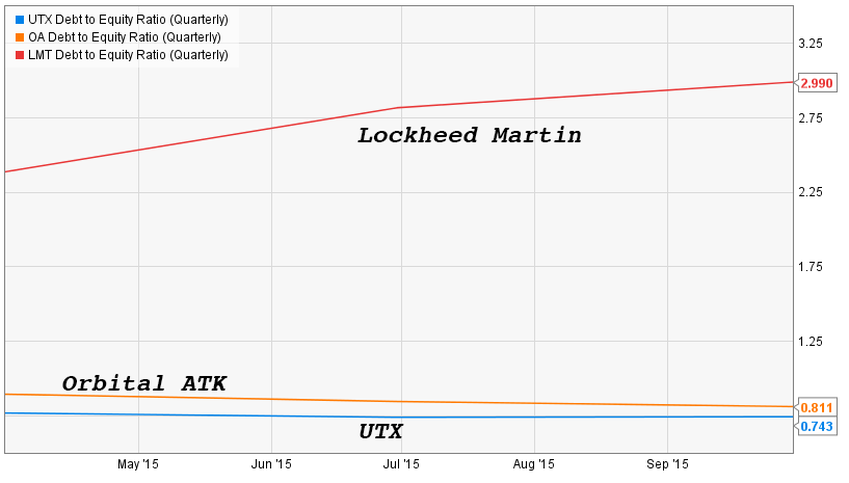

Debt-to-Equity Ratio

Three aerospace and defense companies. The two on the bottom are in different Penn Portfolios. We do not own Lockheed Martin. The debt-to-equity ratio was one data point in our decision process.

Suppose a loan officer at a bank had two afternoon appointments. One was with John, and the other one with Susan—both of whom were applying for personal, unsecured loans. According to the information gathered on their respective balance sheets, John had $100,000 in total assets, but he also had loans (mortgage, credit cards, etc.) with an outstanding balance of $200,000. John’s debt-to-equity ratio (D/E) would be 2.00 (or 200%).

Susan, on the other hand, shows $1 million in total assets. Like John, she also has $200,000 in outstanding debt. Her debt-to-equity ratio would be 0.2 (or 20%). If the loan officer had to choose one person to give a loan to based on this information, who do you think it would be?

The debt to equity ratio is an important tool when gauging a company’s overall financial health, but it cannot be evaluated in a vacuum. For example, a company might be highly leveraged, but it is using that borrowed money to build a new plant that will greatly increase the firm’s profitability. Ironically, AppleAAPL, which has a low debt to equity ratio, has been criticized by some activist investors for not being more aggressive with its financing.

With the ultra-low interest rates of the past several years, debt-to-equity ratios have climbed as companies have taken on more debt to take advantage of lower rates. The opportunity costs associated with using borrowed money were less than if they dipped into their own cash hoard, which is why a company like Apple might borrow to fund an acquisition instead of taking a bite out of their $200 billion rainy day fund.

Consider a startup company. It has created a great new product or service, and has been successful at selling this amazing product/service by word of mouth. The company wants to go nationwide, however, but that will cost a lot of money. When they get the funding, their debt to equity ratio is going to be astronomical, but once the money starts flowing in, that percentage should drop rapidly.

This example buttresses an important point when comparing different companies and their D/E ratios. In a high-growth industry like biotech, it is normal to see D/E figures of 4 or 5 or even higher. In a slow growth industry like insurance, however, those numbers would send up serious red flags. In short, even though a company has a large D/E, it simply means that further research is needed to figure out why the condition exists. Sadly, in too many cases, it is simply financial mismanagement.

Which brings us to something very important to watch for as interest rates rise. As alluded to in Liftoff at the Fed (an accompanying article in the Journal), the US government wants to keep rates as low as possible to avoid a higher servicing fee on the country’s $19 trillion in outstanding debt. The same holds true for overleveraged companies. If rates escalate quickly and old debt must be refinanced, these companies will either A) be forced to pay more in interest, or B) fail to qualify for new loans as standards tighten. Either way, it could spell disaster. Is anyone in Washington listening? We didn’t think so.

(Reprinted from the Journal of Wealth & Success, Vol. 4, Issue 2.)

(OK, got it. Take me back to the Penn Wealth Hub!)